He finally decided that he did not want to die in Kokomo. He couldn’t bear the idea of being buried there. So he moved to Cicero, a much more tolerant town in the same state. I believe that Elton John helped his family with the down payment for the new house.

We met Ryan, then 15, right after he moved in. It was a very humid, 90-degree day in July. We walked into Ryan’s house and it was stifling. He was 55 pounds or so, this tiny person whose growth had been stunted by the hemophilia and then by the AIDS. And he had a blanket over him. He’d go over to the stove, turn it on and warm his hands.

He was very, very shy and very suspicious of us. He had had many unpleasant dealings with the media. He felt like he had been at the center of a freak show. On the other hand, he felt that it was important for people to start learning what AIDS was really about - - how you got it and how you didn’t.

We were low key. I didn’t even take my cameras out for the first four hours. We weren’t going to do anything that made him uncomfortable. We ending up spending the whole day, and Ryan ended up being on People’s cover.

Soon, we found ourselves invited to document Ryan and his family, off and on. Within months, his life would be totally transformed. His doctor said it was not because of the medicine but possibly because of the love he was given. His neighbors started knocking on his door, saying, ‘’Welcome to Cicero.’’ The superintendent held an all school assembly before Ryan arrived, insisting, ‘’We will not treat Ryan White like the people of Kokomo did.’’ The everyday contact of his peers was now supportive. People readers wrote to him, saying how much they admired what he was doing. When writer Bill Shaw and I went back again, eight months after our first story, Ryan had become much less guarded. He had gone from being the outcast to being someone who was respected had made a tremendous difference in his life.

Soon, we found ourselves invited to document Ryan and his family, off and on. Within months, his life would be totally transformed. His doctor said it was not because of the medicine but possibly because of the love he was given. His neighbors started knocking on his door, saying, ‘’Welcome to Cicero.’’ The superintendent held an all school assembly before Ryan arrived, insisting, ‘’We will not treat Ryan White like the people of Kokomo did.’’ The everyday contact of his peers was now supportive. People readers wrote to him, saying how much they admired what he was doing. When writer Bill Shaw and I went back again, eight months after our first story, Ryan had become much less guarded. He had gone from being the outcast to being someone who was respected had made a tremendous difference in his life.The impact of that first story was significant. A major magazine was addressing the topic of AIDS head on. The pictures showed really sick people. It was not reassuring. But it came across in an open, sympathetic and honest way. The pictures said that people with AIDS were human beings. And one of the reasons I work for People magazine is because if there is any segment of the country that need to know about these issues - - Middle America, the audience that People hits. Anyone, gay or straight, rich or poor, of color or not, could look at those pictures, feel what Ryan was going through, and make that jump, that this could be my kid, my brother, my sister, my parent.

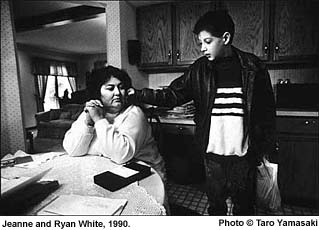

After our second story, Ryan and his mom, who had been extremely reluctant the summer before, said that they felt happy with their decision to open up and be in People. It had made a tremendous difference in their lives because it helped others see them as they were, rather than as pariahs. And you could see that in the pictures. Ryan playing with his dog. Ryan with his good friends playing pool. Ryan hugging his mom. The two of them praying at bedtime.

We did a story on his mother Jeanne’s trials. We spent a lot of with Ryan. We traveled with him to Omaha, where he got the keys to the city. We were getting to be friends, all of us. Ryan was named one of People’s 50 most beautiful people. But his health, by 1990, was getting progressively worse. And I got a call from Jeanne. ‘Ryan‘s dying. You and Bill are the only journalists who are going to be in the intensive care unit with us. Please come as soon as possible.’’ We rushed to Indiana.

There must have been 75 journalists downstairs in one of the waiting rooms. Ryan was a huge story by then. Ryan was in a coma when I got there. He never regained consciousness. Jeanne said, ‘’Please don’t photograph Ryan’s face, I don’t want to remember him like this.’’ He was very swollen. And that’s why the photograph you see of Jeanne and Elton John, at Ryan’s bedside, does not include Ryan from the neck up. We were there for maybe nine days and Elton John was there the entire time. Elton was really taking care of the family. He was sorting the mail. He’d come in with a sack full of toys he would distribute to other kids in the intensive care unit.

There must have been 75 journalists downstairs in one of the waiting rooms. Ryan was a huge story by then. Ryan was in a coma when I got there. He never regained consciousness. Jeanne said, ‘’Please don’t photograph Ryan’s face, I don’t want to remember him like this.’’ He was very swollen. And that’s why the photograph you see of Jeanne and Elton John, at Ryan’s bedside, does not include Ryan from the neck up. We were there for maybe nine days and Elton John was there the entire time. Elton was really taking care of the family. He was sorting the mail. He’d come in with a sack full of toys he would distribute to other kids in the intensive care unit.That entire week was pretty remarkable for me. I wasn’t just a photographer, but a friend caught up in a story. When Ryan died, everybody went into his room and held hands around the bed. I was in there with a camera. And Jeanne said, ‘’Taro, you can take the picture or you can join us.’’ And I put my camera down and I joined the circle. I knew that was an important picture. I knew that it was a moment I should ‘get.’ But I also knew that the reason I was in there in the first place was that they were not thinking about me as a photographer and I was not relating to them as a photographer. I knew I was going to wish I had taken that picture on some level but I just felt like I had to join that circle.

The experience really made me think a lot about my humanity, the importance of the pictures I take, the role photographers can play as educators. That’s basically what photojournalists do: They experience something and then they communicate it, in still images, to a larger audience. But I really believe that I’m also educating myself. And I guess there are certain things more important than ‘getting the picture.’ There’s a relationship with the circumstances and the individuals and their interplay around you. And it became very clear to me that there are certain things that I can’t photograph. I don’t have that killer instinct. Yes, I’ve gone through hell to get some pictures. But on the other hand, this is a picture I passed up. And I would do it again.

I was just in Croatia last summer doing a story on this summer camp for kids in war zones that brings Croatians, Serbians and Bosnians children together. Volunteers from all over the world were there. And there was a teacher from Connecticut. She heard I was from People magazine. She met me and she asked, ‘’What is the most important story you’ve ever done? What hit you the hardest on a personal level?’’ I thought a while and answered, ‘’The stories I did on Ryan White.’’

Taro Yamasaki

.jpg)